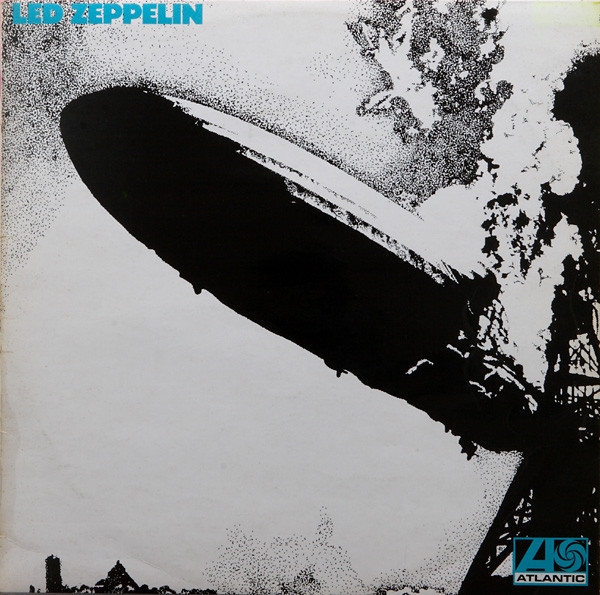

Led Zeppelin

Led Zeppelin

| Release date | Label | Producer | Genre | Length | More info |

| 1969.01.12 | Atlantic | Jimmy Page | Early Heavy Metal | 44:52 |

|

Where Blues Magic becomes Black Magic, and you don't even know it.

Background

When discussing great bands, we rarely focus on the fascinating entanglement of necessity and chance that rules over rock music just as sternly as it rules over any other aspect of the universe. Listening to Led Zeppelin's debut and mentally comparing it to all the other bands that hanged around in late '68 / early '69, I can't help wondering - as inevitable as it may have been for a band like that to appear out of the proverbial blue, couldn't it have happened... differently? What if these guys stumbled across another lead singer, say, somebody like Rod Stewart, or Roger Daltrey? Or a different drummer - professional, enthusiastic, inspired, but not John Bonham? Or another bass player, one fully committed to the band's mission, but without as deep an understanding of the guitar / bass symbiosis in this new kind of music as demonstrated by John Paul Jones? Change but one ingredient in the pot, and Led Zeppelin might become somebody else - Vanilla Fudge, Steppenwolf, Steamhammer, Grand Funk Railroad, one of those innumerable heavy bands of the epoch that are all enjoyable and worth remembering every now and then, but could never boast the chemistry level of this special concoction. And it's not as if Led Zeppelin had some sort of lengthy, pre-planned, meticulously implemented gestation period - they just got together in the fall of 1968, played ʻTrain Kept A-Rollin'ʼ, and that was it. Magic in the air and all that.

Perhaps Led Zeppelin did not "invent heavy metal", if one insists upon a technically narrow understanding of heavy metal that completely disentangles it from "heavy blues"; in this case, the progenitor is Black Sabbath, and the harmony structures are more rooted in pop and, ultimately, even in classical music. Another argument is sociological - "heavy metal" is often viewed as a relatively closed genre in itself, where musicians rarely borrow from outside influences and keep to their own "metal community" rather than mingle with the crowds at Woodstocks and Glastonburies (unless they sell out like Metallica), and Led Zeppelin never really followed that trend (after all, Jimmy Page was originally from the pop/rock crowd, and would always feel more at home with the likes of Clapton, Beck, and Townshend, than, for instance, with the New Wave of British Heavy Metal guitarists). However, it may be argued that heaviness of pop music as a concept truly originates with the work of Zeppelin: where their predecessors such as The Who, Cream, and Hendrix were more concerned about externalizing their energy, focusing on anger, exuberance, in-yer-face arrogance as the emotional cornerstones of their music, Led Zeppelin were the first ones to successfully internalize it, making music that didn't just come in huge, but understandable shockwaves at you, but somehow pulled you inside the darkest corners of their (or your own) subconscious, corners in which you are normally disinclined to penetrate. In this, they were more the legitimate followers of The Doors than of The Who or Cream, and while they may not have trumped The Doors in terms of melody or artistic sincerity, they certainly had them beat in terms of sound - because where "heaviness" was concerned, Led Zeppelin worked as a perfect team, unlike The Doors.

Like so many other people around me, I used to poke (sometimes rather mean) fun at how Led Zeppelin would shamelessly steal other people's material in those early days - their blues, folk, and pop "rip-offs" came at a steady pace and were, almost doubtlessly, aimed at maximizing cash flow (and I'm pretty sure that manager Peter Grant was always behind that scheme as well). Obviously, that was not a good thing: Chicago bluesmen and Greenwich Village folkies deserved their rightful share of the cuts, and it wouldn't have hurt the boys' ego to share. Nor does the argument of "they were simply doing the same thing that people in the blues/folk tradition had been doing for hundreds of years before" really hold water, because copyright standards had changed significantly by the mid-20th century, and ever since the proliferation of sound recording, the artist's right to his art had become much more clear and formal than it used to be. However, if but one exception to the rule could be made, I would have gladly granted the exclusive right to Led Zeppelin - who not merely made others' songs "their own", but transformed them into such completely different entities, it would be like taking somebody's pet lizard and genetically mutating it into an Alien. They needed these holy blues structures, yes, and they didn't care that much if the base chords they used were their own or were strung together by anybody else - the thing is, with a band like Led Zeppelin, everybody is an essential part of the creative process, even the drummer.

Again, as the Sixties flow ever farther out of our memory reach, it becomes harder and harder to understand just how much impact the appearance of Led Zeppelin made on the musical and cultural scene in 1968-69. To do that, you'd have to immerse yourself in a lot of music from that period, including the best and hardest rocking stuff, and then, once all the drum beat styles and all the guitar tones of that period have been made known to you, come back to the self-titled debut. Nothing, not even Hendrix, compares to it in terms of the overall depth of sound, and claims that "Led Zeppelin opened the doors to the Seventies in 1969" are not that far away from the truth. Yet, in a way, it was really an accident. What if the Yardbirds hadn't fallen apart in 1968? What if the band had settled on a drummer less brawny and powerful than Bonham? What if Atlantic Records had saddled them with their own producer? Would the Seventies have never come then?.. (For that matter, am I the only one to think that the band never looked as beautiful - physically - as it did in late 1968/early 1969? All those bare chests, glam outfits, and cocaine eyes of the early 1970s are really not my style).

Some basic factsPeter Grant, the band's manager, was always extremely careful about promotion - an evil, arrogant, and fanatically devoted marketing genius - but, just like there was only so much a Brian Epstein could do to enhance the immense talent of the Fab Four, so would all the marketing devices of Peter Grant and Atlantic Records have gone to waste if the chemistry between Led Zep members did not happen to be precisely the thing that the general public needed at the time. The record was their only one not to hit No. 1 in the UK (in the US, Led Zeppelin IV also only got to No. 2), but it still climbed all the way up to No. 6 in the UK and No. 10 in the US - thoroughly impressive for a band that nobody had even heard of up till then. Ironically, critical reaction (including a condescending review in Rolling Stone) would rather seem to go against the band: with heavy rock in general not being in much fashion among contemporary critics (who preferred "rootsy" stuff and anything that drifted towards the "intellectual" aspect of rock), Led Zeppelin found themselves the target of much press ridicule. Actually, while we can sneer and jeer at this now, it is still refreshing to look back at a time when huge commercial success could go hand in hand with a healthy-skeptical press reaction, and even that original Rolling Stone review by John Mendelsohn, from a certain angle, had a point - as much as Led Zeppelin brought to the table, it was perfectly legit to deride their contribution as ridiculously excessive.

From a modern standpoint, of course, Led Zeppelin are unassailable: their popularity has endured, their legacy is legendary, and all the critics have long since paid their dues. Furthermore, this self-titled debut, long regarded as a good, but "formative" Led Zep album, also seems to have finally come into its own, with more and more people coming to regard it as, if not the best Zeppelin that money can buy (no amount of revisionism can probably move the mountain of Untitled), then at least as a fully realized, completely self-sufficient and authoritative record in its own rights. With the band's blues side, folk side, pop side, and experimental side all well represented throughout the record, the only thing it does somewhat lack are original melodies - but then again, with the way Jimmy works, you can never really tell when something is an original melody with him and when it's an artistically legitimized rip-off, anyway.

For the

defense

One of the accusations that is often hurled at Led Zeppelin by people who refuse to listen really hard is that there's too much "generic blues" on the album. Well, first and foremost, Led Zeppelin has always been a blues-based band, so it's basically all a matter of how many interesting sonic ideas they throw in the pot. As far as I'm concerned, one listen to ʻYou Shook Meʼ compared to Muddy Waters' and Willie Dixon's original - or even to the magnificent Jeff Beck/Rod Stewart cover (which "accidentally" came out exactly one month prior to Led Zeppelin getting in the recording studio) - should be enough to put aside any silly accusations of "genericness". The combination of Page's "banshee" guitar tone, Jones' drawn-out, poisonously-fuzzy downtuned bass, Bonham's drumming where each subsequent kick bashes in yet another skull of a downtrodden enemy, and Plant's "on-the-brink" vocalizing - basically, this gives the idea of "giving it their all" a whole new meaning. Of all four-piece bands at the time, probably only The Who could have that level of dedication, but The Who had a different agenda, not focusing on the "led" in the first place.

One thing that I have to confess is that I never, ever found that much "sexiness" in the band's music. The undeniably sexual nature of the blues music that they were appropriating and subjecting to their own purposes turned into something much darker and deeper: after all, Jimmy wasn't into black magic and all that Crowley stuff for nothing, and I'm fairly sure that his own love for Chicago blues was far more related to nurturing his own "dark side" rather than his wet dreams and the basic need to score. (That certainly did not prevent the band from their famous sexual escapades once they got the freedom and the finance to do this, but hey, music is music, and free pussy is free pussy, right?). This is why it doesn't really matter that for ʻYou Shook Meʼ, Plant mixes together seemingly disconnected lyrics from several blues tunes (including the "bird that whistles" bit from ʻCorrine Corrinaʼ) - this is not really a song about having wild sex all night long; it's a song about getting in touch with the naughtiest, nastiest, most evil parts of your soul, and this is the one and only reason why the song needs to have all these brutal drums, grumbling-bellowing bass lines, and Plant singing in unison with the arching plummet of the guitar line as both tumble off the cliff straight to hell. Does this sound a little cartoonish? Maybe it does, but it is also totally believable. Remember, any time you feel yourself attracted to ʻYou Shook Meʼ, you pretty much go drag racing with Satan. That's what makes it so much fun. Generic blues? Nah, you're not copping out of the frying pan that easily.

The "descent into Hell" is, of course, even stronger accentuated by the bass line of ʻDazed And Confusedʼ (which was, in an embryonic way, already implanted in the ripped-off Jake Holmes original, but, as with most of their rip-offs, only hinted at the potential). Again - is this merely a song of betrayal and torn feelings, or are the lyrics merely a meaningless front for a chill-sending dark ritual? As far as I'm concerned, everything about this six-and-a-half minute mini-suite (not to mention its famous expanded renditions in concert) screams HELL, culminating in Jimmy's bowed guitar parts that are evil incarnate, something you'd expect to be performed at the crossroads at midnight (with the bow strung with a dead black cat's sinews, no doubt). Remember the fast part and Plant's wailings over the madly screeching guitar? That's one hell of a Walpurgis night for you. Basically, on this and just about any other of their blues rants, what this band does is it takes the sex out of the blues - and puts the Devil in it. They used to shun Afro-American music for that, associating it with the Devil when most of it was really just about getting laid (which is okay, since for traditionally rigid white Christian culture, getting laid is about the Devil) - now, ironically, they're getting it back from their own bunch of white boys, totally possessed and loving every second of it.

And this is also why most of their ballads are tragic, or at least sound tragic even when the lyrics aren't so directly: it's all about the Fall, about Paradise Lost, about some vague, faint memory of bliss rather than bliss itself. Here, the approach is blunt and direct, with ʻBabe I'm Gonna Leave Youʼ, much like the hard rock songs, also based on descending patterns and doom-laden atmosphere. I always lose count just how many times the quiet mournful parts alternate with the loud hysterical ones, but the fact remains that as of 1969, this was probably the most emotionally draining, devastating statement of The End put on tape. It's not a song about dumping your loved one and getting along like the ramblin' man you're supposed to be - it's a death knell, and the final "That's when it's callin' me... I said that's when it's callin' me back home..." is the final expiration after the long, torturing agony. Think of this - think of it all as a last confession of someone lying on his deathbed, raving about how "we're gonna go, walkin' through the park every day...", and it suddenly becomes chilly, creepy, and perhaps even too scary to play when you're not feeling all that good.

Next to that immortal trio of songs on the first side, the rest of the album feels either a little slight in comparison (the short pop songs), or a little superfluous (ʻHow Many More Timesʼ is basically a revival of the general vibe of ʻYou Shook Meʼ), but the pop songs serve as short, concise, and catchy energy bursts in between the dark epics, and what with Bonham's masterful drumming on ʻGood Times Bad Timesʼ, or Jones' careful organ work on ʻYour Time Is Gonna Comeʼ, I couldn't ever call them ineffective - they just don't work too well on their own, outside of the album's general context, or, perhaps, they don't sound like songs that could be owned exclusively by Led Zeppelin and no one else (it is hardly a coincidence that ʻYour Timeʼ would not be performed live by Jimmy Page until he teamed up with The Black Crowes in 1999). Still, the coda to ʻGood Times Bad Timesʼ clearly presages the swagger of ʻWhole Lotta Loveʼ, and the acoustic picking on ʻYour Time Is Gonna Comeʼ (blending in with a stylistically similar pattern on ʻBlack Mountain Sideʼ) presages the folk-fest on Led Zeppelin III, again, showing that almost all of Zeppelin's future directions were already previewed and tackled in some form on their debut.

Of the heavy songs, one that is completely free of any "devilish" overtones is the breakneck-speed ʻCommunication Breakdownʼ - coming as a sort of blueprint for both Black Sabbath's ʻParanoidʼ and Deep Purple's ʻHighway Starʼ with its chug-chug-chug-break-chug-chug-chugging rhythm (it was also quoted as a major source of inspiration for Johnny Ramone, hence, a milestone for the evolution of both heavy metal and punk rock). Even so, Plant does a good job at building up the "going insane" vibe, rather than turning it into a party fun rock'n'roll anthem or a pissed-off misogynistic garage-rock sneer, and even with all of the "I want you to love me all night", this feels like the explosion of a madman rather than the overflowing libido of a sexual maniac (sorry Robert, I know you tried). And, let's admit it, this is why the album's special: were it all just about letting rip with implied sexual energy, it would have remained on the level of AC/DC, but the boys constantly work well above that level. Or "below", considering how many trips to the depths of Hell Page's and Plant's minds must have taken over those several weeks of September-October 1968.

For the prosecution

A part of me still sort of wishes they'd have taken a little more time on the album. For instance, I have never been a big fan of ʻI Can't Quit You Babyʼ - unlike the case of ʻYou Shook Meʼ, here they seem to not have been able to find a properly unique sonic angle, and the result sounds not too unlike the typical average heavy blues cover of the time (though Bonham still does an exceptionally mammoth job on the drums); as far as slow, desperate, soul-burning blues numbers go, this one would be very soon rendered completely obsolete by ʻSince I've Been Loving Youʼ (where they did find an exceptional sonic angle). On the other hand, ʻHow Many More Timesʼ, while on the whole an excellent reinvention of the Howling Wolf vibe, is somewhat redundant after ʻYou Shook Meʼ and ʻDazed And Confusedʼ (and repeating the bowed guitar trick was completely unnecessary - once was just enough); it is only saved by its multiple sections, with even a bit of ʻBeck's Boleroʼ thrown in, meaning that nobody is going to get bored, but overall it's kind of a "okay, we're out of fresh ideas, now let's take almost everything we did here on the album and briefly repeat it one more time" approach.

Mind you, this is not a scathing criticism - the sonic potential of a fresh young Led Zeppelin was so huge that even hearing them "coasting" like this is a delight. But this is the kind of stuff that does give the album its unjustified reputation of "formative", not because they didn't have their schtick worked out already (they did), but simply because they weren't given enough time to capitalize on it fully. Other than that, I cannot blame Led Zeppelin for anything much - and it does have the added benefit of Robert Plant not yet going overboard with incessant obnoxious ad-libbing (a problem that mostly showed itself in concert, but would already be mildly spoiling some of the band's studio work as well).

Conclusion

| Melody | Voice | Mood | Production | Innovation/Influence | Where it belongs | RYM preference | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#42 (Oct 16, 2016) |

| Previous entry | Main page | No next entry |