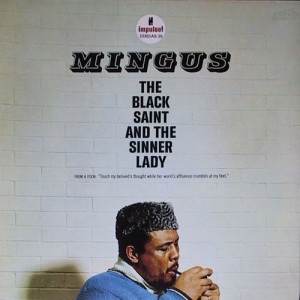

Charles Mingus

Charles Mingus

| Release date | Label | Producer | Genre | Length | More info |

| 1963.07 | Impulse! | Bob Thiele | Art Jazz | 39:25 |

|

You keep your psychedelic jazz - I'll take psychiatric jazz instead.

Background

Although I have yet to familiarize with much of Mingus' early output that precedes this album, I am well acquainted with such masterworks as Blues & Roots and Mingus Ah Um - and as great as they are (and on a pure gut level, I probably enjoy both of them more than The Black Saint), it is still a bit of a mystery how those early styles could eventually sprout into the visionary musical jungle of 1963. Mingus is one of my favorite jazz people, primarily for two reasons: he is a master tunesmith (as opposed to master improviser), and he has an indomitable ferociousness to him that should inevitably bring the man closer to the hearts of jaded rockers or fans of gritty Chicago electric blues - when he's at his best, his music burns and explodes, instead of smoothly flowing as it does with so many other jazzmen. But behind all that composing talent and the ability to play bass like an artillery piece, there was also gigantic ambition, a desire to elevate jazz music to artistic heights and symbolic depths that Miles Davis could only hint at, and that Duke Ellington could not possibly attain for fear of becoming too inaccessible for his audiences. The time was early Sixties, with change in the air, and the place was The Village Vanguard, with young people of all creeds and colors living and breathing that change - and of all people, Mingus would be the man to erect the Taj Mahal of jazz music. Or, at least, such was the plan.

Of course, to do that, Mingus would have to move beyond jazz proper: The Black Saint is commonly acknowledged as a synthesis, owing almost as much to classical influences of all sorts (and more than a little bit of folk music, too). At its heart, though, we have an unmistakably Afro-American core: this is black music appropriating elements of white culture, repaying that old debt to Ravel, Gershwin, and the like - in fact, the very definition of the record as a "jazz ballet in four parts", yet a ballet whose choreography rests entirely in the mind, is a good indication of what the man had in mind. Take the "wildest", most Dionysian form of music devised by the white man, fill it with the "wildest" musical content ever thought of by the black man, and thus, symbolically get the old white vessel inseminated by the new black spirit - prove to the world that jazz music is not just good for basic entertainment and groove power, but that it can have as much emotional depth and psychologism to it as anything that has its roots in white European civilization. Of course, with all the jazz masterpieces made in the previous decades, you'd think this point no longer needed proving, but, in all honesty, jazz in 1963 still needed an "epic" dimension to it, something of the Wagnerian-Mahlerian kind, or, heck, even something of the Stravinsky kind. Its own Rite Of Spring, so to speak. Why it was Mingus and not Miles or Coltrane or Thelonius Monk to come up with that idea, we can only guess. But it sure is damn lucky for us that it was Mingus, in the end.

Some basic factsAnd they were befuddled - a bit of digging will show that contemporary reviews were mixed, with many critics acknowledging they were clearly listening to something completely different, yet few of them were willing to hail that difference as an exciting, consistently emotional breakthrough. Some of the formulas preserved from that era, in fact, recall some of the similarly scathing (though much less politely stated) reaction critics had to progressive rock in the early 1970s - hardly a wonder, because if any album deserves (by retrospective analogy) the title of "progressive jazz", it is this one. A single suite in four parts, with the fourth part consisting of three movements and occupying an entire side of vinyl? Subtitles like "Of Love, Pain, and Passioned Revolt, then Farewell, My Beloved, 'til It's Freedom Day"? Leitmotifs? Overdubs? Pretentious liner notes with mentions of Freud? No wonder even back then some people may have preferred the much more direct and visceral aural schizophrenia of Ornette Coleman and other avantgardists, I guess. That said, one should not overestimate the mixed/negative reaction, either: all in all, the record still made an immediate impression, and the main reason why some people felt uncomfortable about it might have had to do with the fact that, due to its original planning and execution, Mingus could not really perform it live, let alone entertain any idea about choreographing it and actually taking it to the opera house. As time went by, though, the album inevitably grew in stature at a rapid pace - today, there's a core consensus about it being Mingus' topmost achievement, one that took so much spirit and energy that he could never truly rise to the same heights of expression ever again.

For the

defense

How should we go about this, I wonder? It is hard to write "easily accessible" reviews of jazz albums, and double hard to write reviews of "classical-jazz synthesis" like The Black Saint. Let alone the fact that hundreds of pages of text have already been written about it, with all sorts of perspectives on how to decode its instrumental symbolism, the enigmatic lines of the track subtitles, and the consecutive emotional currents of its several movements - I myself remain quite confused by its scope and sheen. I will not pretend to be "deeply moved" by its allegedly tormented / haunted sound: I find it much easier to be moved by the "hard rocking" side of Mingus on his earlier records. But there's something different here: the record leaves behind a lot of strange, hard-to-classify impressions and memories, an intrigue that will probably always stay an intrigue.

Once the whole thing is over, close your eyes and try to remember what you can about it. Most likely, it won't be any specific theme, hook, etc. (although repeated listens bring out some of that, too) - it will be the atmosphere created by the small host of brass players. A hot, dusky, sweaty atmosphere, smelling of New Orleanian bayous as much as it smells of African tropical forests - and it is hardly a coincidence that the tempos consistently remain so slow (whereas on so many other records, Mingus would distinguish himself by playing at the most insane breakneck tempos at the time), and that the time signatures so frequently take on a "crawling" attitude, because to me, the album is best seen as the allegory for a slow, exhausting, painful journey through dense, hot, mystically enchanted, and somewhat hostile territory: think a black King Arthur slogging through the marshes in search of that goddamn Lady of the Lake, which, of course, cannot be found until he fights off packs of hungry alligators (a.k.a. his inner demons). I'm pretty sure Mingus himself did not see it quite that way, but he might have agreed that the slow and repetitive nature of so many of the grooves, and the near-constant "sighing" and "moaning" and "groaning" of the brass parts are emblematic of a dull, mind-numbing, always-be-there-with-you kind of pain that is downright impossible to shake off. Sometimes the music accelerates and you begin going a little mad with that pain, but these fits are temporary - whereas "routine suffering" is permanent.

This is quite important, actually. The Black Saint ain't a Dionysian celebration - it might be indirectly influenced by Stravinsky, but it does not seem to me to be symbolizing the wildness of the spirit, more like a gentle spirit trapped in the wild(er)ness. This is best felt on tracks like ʻDuet Solo Dancersʼ, which begins very peacefully, with a soothing piano ballad part and a gentle brass-led dance part; then, two minutes into the piece, tubas, trombones, and trumpets announce a complete mood overhaul, as if some creepy Nazgul just cast his shadow over the idyllic setting, and everybody has to run for cover, with harmony very quickly subdued by chaos. Eventually, the sun comes out once again and things revert to normal, but there's no knowing what sort of internal damage has been done all the same. Gentleness, tenderness, and incurable melancholia dominate ʻGroup Dancersʼ, which probably introduces the single most memorable theme on the album (later reprised in ʻMode Dʼ) - gradually growing out of Mingus' own piano introduction, it might be the saddest bit of waltzing ever put to tape; on the whole, the piece has a certain Schumann-esque vibe, criss-crossed with the Andalusian freedom lover's sorrow (flamenco guitar and all) and, occasionally, with fits of avantgardist madness that come and go, but always feel like interludes - if parts of this or any other tracks feel like barely controlled chaos, they have their own rational place in the whole and never turn the music into reckless avantgardism for avantgardism's sake.

The message of the "journey" cannot be simply described in terms like "optimistic" or "pessimistic". It's all a series of ups and downs, and there's no set trajectory or predictable outcome - for instance, the entire second half of the big suite on Side B is like a battle between self-reservation and insanity, with each side gaining the upper hand at least several times, until both sort of just collapse from exhaustion at the end (there's no triumphant or tragic coda, just one last sax blast fading away into oblivion). It is not all that relevant if this is in any way related to the "black saint" concept - be it a series of reflections on the plight of the black man in general or Charles Mingus in particular - because it is, above all, an exercise in spiritual turbulence that can be tried on by anybody who has ever experienced spiritual turbulence. Think of the piano as the soul, Mariano's alto sax as the guiding angel, and all the tubas, trombones, and trumpets as the inner demons, and what you get then is a ballet of supernatural entities as they battle with each other. It might be more "symbolic" and "figurative" in places than a direct reflection of emotions, but then again, I'm hardly the one to judge. In any case, it's fascinating just to observe what's happening, and you don't have to be a great connaisseur of Mingus' many influences in the worlds of jazz, blues, folk, and classical to get involved.

For the prosecution

Okay, so the record does not have a lot of seriously memorable themes (and the ones that it does have tend to swoosh by very quickly), so it tends to get repetitive, and not everybody loves noise-jazz, which does crop up every once in a while. To this sort of criticism The Black Saint is completely immune - repetition is part of the concept, as is noise, and complaining about the melodies being "underwritten" would make as much sense as complaining about "too many notes" in you-know-what. But I do have a more specific and, perhaps, a more intelligent complaint: I do believe that the second side is somewhat flawed, and does not offer a perfect (or, in fact, any) solution to the problem set up on the first side. Ultimately, the big suite introduces very few new elements (same leitmotifs, same flamenco interludes, same moody piano weeping, same noisy build-ups and breakdowns, etc.), and does not have a satisfactory coda - essentially, we are left in the dark as to the ultimate fate of The Black Saint. Is he reconnected in happiness and forgiveness with The Sinner Lady? Or is he eternally damned with no hope of redemption? Or is he left alone to roam the Earth like some black equivalent of The Wandering Jew? Without a big, thunderous resolution, or a lengthy atmospheric fade-out, the suite ends too abruptly - it's as if the man suddenly ran out of inspiration 40 minutes into the show, and just said, "that's it, I quit", and we never really get to know who the murderer was in the first place. And when you're talking ambitious conceptual suites, that's an important criticism... imagine Quadrophenia deprived of ʻLove Reign O'er Meʼ, or, hell, The Rite Of Spring without The Sacrificial Dance, and you can see the reasons for this relative disappointment. Maybe Mingus saw it differently and believed that the final track offers a clear resolution - but that's just not how I feel about it.

Conclusion

| Melody | Voice | Mood | Production | Innovation/Influence | Where it belongs | RYM preference | |

|

× |  |

|

|

|

#28 (Jul 10, 2016) |

| Previous entry | Main page | Next entry |