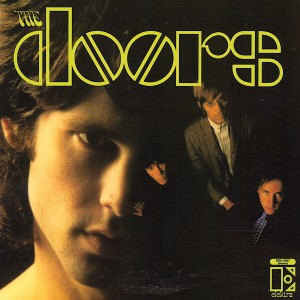

The Doors

The Doors

| Release date | Label | Producer | Genre | Length | More info |

| 1967.01.04 | Elektra | Paul Rothchild | Mope Rock | 44:24 |

|

A shot of Schopenpower-pop for the flower power sop.

Background

Although The Doors' eponymous debut was only released in 1967, they were not, as one might mistakenly conclude, part of the "Sgt. Pepper wave" - the actual recording sessions were held in August, 1966, and many of the songs were already written or at least pre-conceived by mid-'65, when the fateful meeting between Jim Morrison, Artist Extraordinaire, and Ray Manzarek, Gifted Musician, pre-determined the beginning of The Doors and pre-defined their artistic ideology. The thing is, The Doors were never really "part of the crowd": by their very nature as a rock band, they had to appear at festivals and interact with other artists, but more often than not, they kept to themselves; and while you could probably list all of their influences until early dawn (poets, bluesmen, pop crooners, Kurt Weill, Eastern philosophers, etc.), they were nobody's followers - when The Doors appeared on the horizon, people were stunned, having no idea how to put it in its own proper pigeonhole, in spite of all the obvious roots and links.

When you look back at the atmosphere of 1966, you do not really notice a lot of "dark pop": despite the well-publicized connection between rock music and "dark emotions", most of the music from that year tended to be colorful and, if not necessarily optimistic, then at least "spellbinding" in ways that should be opening your mind to the infinite creative possibilities of modern sounds. Biggest hit singles of the year included ʻI Got You (I Feel Good)ʼ, ʻGood Vibrationsʼ, ʻWe Can Work It Outʼ, and ʻYellow Submarineʼ - a gang of uplifting musical rainbows as opposed to only occasional "downers" like ʻPaint It Blackʼ. Many felt that, with all these incredible breakthroughs, the real world was only just beginning: it didn't really seem like the people were ready for a band that would almost exclusively sing about a world that was coming to an end. Into this beautiful dream marched The Doors, veritably the first ideologically armed "anti-hippie" band (forget about Black Sabbath, whose alleged "hatred for hippies" only meant that they wanted to be a very different kind of hippies)... and quickly made themselves as endearing to the hippie crowds as, say, the Grateful Dead.

In a way, the success of The Doors was one of the greatest commercial ruses in history. Based on all we know, Morrison never cared all that much for fortune (as long as said fortune gave him unlimited access to booze, chemicals, and pussy - the three most necessary ingredients for spiritual enlightenment) or fame (although he did like the idea of public artistic preaching as such); his bandmates, on the other hand, happened to be fairly "normal" - and, thankfully, quite talented - musicians who wanted to make great pop songs and earn millions of bucks. By packaging Jim's ideas and words into the shape of immaculate pop masterpieces, they succeeded where so many other "dark loners", from Syd Barrett to Nick Drake to Tim Buckley, ultimately failed: make the music equally respected by the intellectual minority and the less-intellectual majority. Charmed by the catchy hooks, people were buying ʻBreak On Through (To The Other Side)ʼ in droves, believing that this would open their own "doors of perception" to supernatural wonders - by the time they came to realize that there was really nothing beyond those doors other than gloom, loneliness, depression, and death, with The Lizard King presiding over it all, it was too late: they had already pledged their allegiance.

Some basic factsCritical and commercial success arrived almost immediately: ʻLight My Fireʼ went to No. 1 on the charts, the LP itself went to No. 2, and, compilations aside, as of now The Doors remains the band's best-selling album ever, and regularly comes in at No. 1 in average rankings, as well as features in all sorts of top listings for "greatest albums ever". This is a direct, ongoing reverberation of the initial ruckus, when the album's success made Jim Morrison as much of an overnight celebrity as Hendrix, and opened the, ahem, doors for miriads of mopey followers - regardless of whether subsequent records matched, equalled, or fell behind The Doors in general artistic qualities, they were already incapable of producing a comparable shock wave effect.

To the best of my knowledge, there are no significant bonus-filled reissues of the original record: the "40th Anniversary Edition" is said to have been thoroughly remixed, and includes, among other things, a "speed-corrected" version of ʻLight My Fireʼ (a bit faster than the version to which we are accustomed, but I like it slow, thank you very much), as well as some early demos for ʻMoonlight Driveʼ and ʻIndian Summerʼ; but the surviving Doors usually empty their vaults in the form of special archival albums anyway, so there's not much sense in hunting for a tiny handful of inferior bonus tracks (it's certainly not the Kinks or the Who we're talking about here), most of which were already available on The Doors Boxset anyway (an essential release that actually gives some detailed insight into the band's early origins).

For the

defense

A typical history of appreciation for The Doors should, I believe, respect the Hegelian triad. At age 12, you adore The Doors for Jim Morrison and his spiritual guidance of your teenage neuroses. At age 20, you get to despise The Doors for Jim Morrison and his plebeian interpretations of William Blake for 12-year old neurotic teenagers. However, if you happen to be stuck in that phase by the respectable age of 30+, you, my friend, are really no better than a 12-year old neurotic teenager yourself - because that's precisely the time when you should understand that even at age 12, although you didn't really know it, you were actually attracted to The Doors not because some schizophrenic guy from Florida wrote some creepy lines about your mother and father and howled them out, using leather pants as a resonator; you were attracted to The Doors because The Doors were a band, pooling fortuitously vast amounts of individual talent into one large collective vat and feeding off each other's ideas and energies.

The majority of the songs here follow, quite rigidly, the typical pop song format - verse, chorus, bridge, solo, rinse and repeat for about three minutes - with but two exceptions, strategically placed at the end of each of the album's sides so you could easily end the experience prematurely if you are not a fan of anything that goes over three minutes. They're catchy pop songs, too, and trying to insist that Morrison really had no hand in crafting the album's hooks is pointless, because the vocal melodies were his sole responsibility. They're mostly about dark subjects, too - just about any of them sounds like it may have well been written in a prison cell, by some modern day André Chénier with but hours left to live. But most importantly, they are fabulously performed, meticulously arranged, suspensefully crafted pop songs - in all honesty, I cannot think of any other band from that epoch, with the obvious exception of the Fab Four, that would invest so much in the progressive layering of the songs and earn such a huge payoff.

Fans of progressive rock tend to dismiss the short pop song because of its repetitiveness - one or two musical ideas put on predictable replay to generate an ear-worm - but that argument simply does not work with The Doors: nearly every one of these short pop songs is not an exercise in simple repetition, but a dynamic build-up, gradually extending in scope and increasing in temperature until the whole thing goes up in smoke. Nowhere is this seen more effectively than on the opening ʻBreak On Throughʼ. Its melody, if you think long enough on its origins, is not far removed from Bo Diddley's ʻDiddley Daddyʼ (not surprising, given that Bo was one of the band's major influences - they used to regularly do ʻWho Do You Loveʼ in performance), but it's not only being downtuned and made far heavier - it's completely dominated by Robby's increasingly aggressive guitar parts, gaining in strength with each new verse until, by the time they hit the climactic last one, he is hammering out frantic power chords to match the proportionally growing hysteria in Jim's voice. This is the first, and one of the best, examples of their shamanism - a quick, hooky setup, a get-in-the-groove ceremony, and a gradual acceleration of the rotation chair until you lose all control over yourself. And at the same time, the song ends on such a symbolic note - as we hit the final race of "break on through, break on through, yeh, yeh, yeh, yeh...", the song is abruptly cut off in mid-air. Instead of some shattering climax, what we get is... silence. Yes, you finally break on through to the other side - only to find out that there is nothing but emptiness, to end up on the threshold of The Great Void. Kind of ironic, though nobody probably paid attention at the time.

Or take the song that opens the LP's second side, an epic cover of Howlin' Wolf's ʻBack Door Manʼ. Had The Doors been Led Zeppelin, they would have probably just renamed the song to something like ʻEat More Chickenʼ and taken all the credit for themselves - and I wouldn't have the strength to blame them, because, well, Wolf and Willie Dixon really just wrote a song about promiscuity (or about anal sex, if you're that kinky); in the hands of this band, it became a song that is at least about The Grim Reaper, if not something creepier. And it does not begin with Jim, either: it begins with the slow, steadily thickening guitar/bass seven-note riff-o'-doom, taking twenty seconds to feed the fire before it morphs into Manzarek's equally unnerving organ melody. In between the verses, you also get a beautifully constructed Krieger solo, wobbling back and forth between "lyrically wailing" melody lines and repetition of the ominous seven-note riff as if the creepy protagonist and his victims (whoever they are) were having a dialog where one begs for mercy and the other shows none. And, of course, there's always the Doors' most efficient trick - let the song deceptively "die down" in the middle, only to have it reignite and explode into total fuckin' fury for the finale. With all due respect to the great Howlin' Wolf, that's not something that he, or anyone in his band, ever gave a thought about, and that is why I never ever get the urge to shut a good Doors song midway through because "I've heard it all already".

The entire record is just soaked with all sorts of aural delicacies, hits and non-hits alike. ʻEnd Of The Nightʼ - that introduction has arguably one of the most amazing soundscapes of 1967. The opening duet of Manzarek's faraway, ghostly organ and Krieger's "deeply sighing" guitar would have been sufficient on their own, but the final stroke of genius is at 0:12, when they are joined by that deep, midnight-like sound of the chimes: I have no idea how they got that effect, but I've never ever heard a comparable sound anywhere, and this little bit is like the ultimate stroke of doom. If the original organ and guitar parts might be said to represent "realms of bliss, realms of light", then the "chimes" are unquestionably "the endless night", a grim, relentlessly recurring symbol of a state where the clock always rings out midnight or whatever it's supposed to ring out. Again, Jim is an integral part of this - as is, for once, William Blake - but the song wouldn't really be worth a nickel if not for its unique, immortal musical arrangement.

Neither Manzarek nor Krieger were virtuosos on their instruments: Ray was about as prolific on keyboards as he was in basketball, economics, or cinematography (all of which he trained in more or less professionally, unlike music), and Krieger had only picked up the electric guitar six months prior to joining the Doors. You can tell it quite well by the lack of speedy/flashy passages on the record and by the relatively simple chord sequences that the guys pick out to play - but where they might lack in fluency or complexity, they see it as their duty to compensate with sheer expressivity, which is probably why I have had the lengthy organ and guitar solos from ʻLight My Fireʼ stuck in my head for years, unlike, say, anything ever played by the likes of Santana or Rick Wakeman. These solos seem pre-composed rather than improvised, with Manzarek sticking very closely to the rhythm and Krieger playing his guitar part like a modern day violin partita, throwing in little bits of Eastern drone, little bits of the blues, little bits of flamenco (which was the first style he'd ever learned) and, indeed, a few classical flourishes to boot - all of them glued together so seamlessly that you never really get the feeling of "oh, he's just throwing all sorts of random stuff in there". For that matter, the instrumental "jam" part, sacrilegiously (but inevitably) cut from the single version, is the best part of ʻLight My Fireʼ, period - the song itself is pretty good, but the "come on baby light my fire" chorus has always seemed to strike a slightly false note to me.

The album also initiates the tradition (adhered to on all but two of the band's records) of going out with an epic rambling pseudo-stream-of-consciousness, and although I've never been as much of a fan of ʻThe Endʼ as I'd adored ʻWhen The Music's Overʼ (for being so much heavier), ʻThe Soft Paradeʼ (for being so much trippier), and ʻRiders On The Stormʼ (for being so much more gorgeous), there's no denying that its 12 minutes are a major musical milestone. Of all of the band's compositions, this one actually comes closest of all to resembling the sound of The Velvet Underground, even though I'm not sure the two bands were ever in touch in their pre-glory days (well, relative "glory" in the VU's case), and, unlike the VU's, the Doors rarely, if ever, toyed with dissonance and "intentional ugliness" - nevertheless, there are some clear links here, not only in terms of overall length, rambliness, and nastiness, but also in terms of Robbie's guitar phrasing, sometimes emulating the sitar and sometimes just droning on in total oblivion. The major difference is in acting and attitude: whereas the VU, even at their most infuriated, exhuded cool, cynical rationalism, ʻThe Endʼ is a piece of rambling delirium. That prisoner I mentioned above, locked in his cell, is finally administered the hemlock treatment, and this is his final rant-and-rave before "the end, beautiful friend", a rant-and-rave where all the darkest drives become uncovered, including the infamous Oedipus complex bit. When you actually see it that way, even some of the cheesiest lyrics ("the snake is old, and his skin is cold", etc.) sort of lose their cheesiness. That said, I do find the instrumentation a bit monotonous throughout - one reason why ʻWhen The Music's Overʼ, which many people unjustly denounce as just a carbon copy, seems more involving is that, in between all the bass / guitar / drum interplay on that one, they managed to create more suspense on the whole.

Overall, the right way of digging The Doors is not paying too much attention to the alleged "depth" of Jim Morrison's message, which is totally derivative of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer anyway, but accessing it in the context of the musical backing. Not that I don't appreciate Morrison's performing skills - he might not be much of a singer, but he is one hell of an actor, or, rather, an artist: "actor" might give the impression of somebody faking it, whereas in Jim's case we really have no reason to believe that he was not actively living out these songs while performing them. But, and I can't repeat this enough times, the main thing is how they all gel together so marvelously as a band. There's a popular misconception out there, based on either Oliver Stone's movie or certain biased accounts, that there was a tremendous gap between Morrison and the other three, that he was essentially doing his own crazy thing and they were trying to catch up or contradict - that is absolutely not the impression that one gets from their best work. Yes, guitars and organs frequently follow Jim's lead, but just as often it is Jim himself taking his cue from, for instance, the relative loudness or quietness of the instruments - ʻSoul Kitchenʼ and ʻBack Door Manʼ being some of the most obvious examples. It's just one of those perfect symbioses, like The Who's on the other side of the ocean.

For the prosecution

Well, I do have to state, once again, that I have always slightly preferred Strange Days over The Doors, and that position hasn't really shifted over the years. The Doors have an Achilles' heel: when they're in their natural environment (the doom-and-gloom one), they're awesome, but once out of that water, their sound can be somewhat... misappropriated. While rushing out this album so quickly, they inadvertently included a couple of tunes that might have, in anybody else's hands, sounded like highlights, but here, sound relatively weak next to everything else. Case in point: ʻI Looked At Youʼ, a catchy pop-rocker that does not, however, have much in the way of suspenseful build-up, not to mention being rather inane lyrically and not a good vehicle for Jim's voice, either - one of their earliest tunes, probably, knocked off when they were still learning the ropes. Only slightly better is ʻTake It As It Comesʼ - again, an excellent pop nugget for a varied collection of pop nuggets, but definitely superficial-sounding compared to ʻBreak On Throughʼ, with which it shares the speediness, but not the darkness / heaviness / suspense aspect. ʻTwentieth Century Foxʼ, too, although its lyrics are actually quite hilarious, somewhat deviates from the path by being a Dylan/Stones-style female character assassination - kind of a cheap (if funny) shot, dear Jim, only saved by the bell in the shape of yet another awesome guitar solo from Robbie.

Do not get me wrong on this count: personally, I quite believe that The Doors never really released even a single truly bad song prior to The Lizard King getting himself a beer. It's just that the best numbers on this record inadvertently create such an impossibly high standard that it is actually a wonder to me how they could have maintained that spirit on 80% of this record (and close to 100% of the next one). In fact, in terms of sequencing, it might have been a good idea to insert a slightly fluffier "breather" in between the horror heaviness of ʻBack Door Manʼ and the surreal creepiness of ʻEnd Of The Nightʼ - who knows? But the fact remains that the songs are a little uneven in quality, which is actually a bit strange, considering they should have been selecting the very best from their backlog for their planned grand entrance on the musical scene.

Conclusion

| Melody | Voice | Mood | Production | Innovation/Influence | Where it belongs | RYM preference | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#19 (May 08, 2016) |

| Previous entry | Main page | Next entry |